Start With The End In Mind

To start with the end in mind means to start with a clear understanding of where you hope your students will end up. Once you know the destination, it is easier to figure out “How will I know if my students got there?” and “What I can do to help them get there?”.

Drawing from the backward design framework (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005), the first step in the course design process is to determine the purposes and goals of the course. Most instructors do this informally; that is, they have in mind the skills, knowledge, and attitudes they want students to gain by the end of the term. Effective instructional design encourages instructors to express these items in measurable and specific ways, so that students have clear guidance about what is expected of them and how their performance will be assessed. These specific statements are typically called learning objectives.

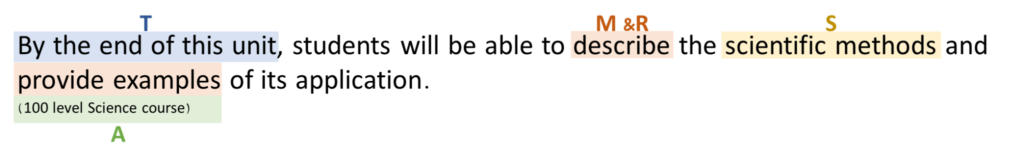

Learning objectives, sometimes referred to as learning outcomes (Melton, 1997), are the statements that clearly describe what students are expected to achieve as a result of instruction. Different from broad learning goals, learning objectives provide clear criteria for instructors to assess whether students are meeting the desired learning goals. Here is an example of how learning goals and learning outcomes relate to each other:

- Learning goal: “I want students to understand/learn/know the scientific method.”

- Learning objective: “Students will be able to describe the scientific methods and provide examples of its application.”

Benefits of Learning Objectives

Well-written learning objectives can be:

A compass for instructors: to guide the design of fair course assessment plans, selection of content/activities/teaching strategies/technologies, and make sure all critical course components are purposefully aligned to support student learning.

A map for students: to see a clear picture of where the course is taking them and what is expected to be successful in the course. Students will be able to direct and monitor their learning throughout the lesson/unit/semester by referring back to the learning objectives.

What Is An Effective Learning Objective?

Learning objectives should be student-centered, describing what the students should be able to accomplish as a result of instruction, rather than what the instructor will cover or do in the course. To ensure your learning objectives are student-focused, it’s helpful to precede your objectives with this prompt: “Upon successful completion of this course/module/unit, students will be able to ____.”

To give students a clear understanding of where they are headed, well-written learning objectives should be Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Result-oriented, and Time-bound (SMART).

- Specific: Good learning objectives break down a broad topic into manageable components, and they are explicit about the desired outcomes related to these components.

- Measurable: As guidelines for evaluation, learning objectives should help instructors decide how well students achieve the desired learning. Much of what students get out of a class happens on the inside or are unseen– students may adjust their perspectives, change their attitudes, and gain new knowledge. But because instructors have no way of directly observing the internal processes of a student’s’ mind, they must rely on external indicators (what the student says or does) to evaluate that student’s progress. For this reason, an instructor cannot evaluate progress based on what the student “learns,” “understands,” “knows,” or “feels.” Thus learning objectives need to deal with changes that can be observed and measured.

- Achievable: Given the resources, timeframe, background, and readiness of the students, objectives should be achievable. The cognitive level of the learning objectives should be appropriate to the course level and student level ( e.g.: a freshman level course as compared to a graduate level course).

- Result-oriented: Objectives should focus on the results, rather than the process or activities that students are going to complete (e.g., writing a paper or taking an exam). A good learning objective will describe the result; the knowledge, skills, or attitudes that students should have acquired within the context of the instructor’s observation.

- Time-bound: Clearly state the timeline if applicable. This can help you decide how well the learners should perform to be considered competent.

Specific – it focuses on the “scientific methods”

Measurable – “describe” and “provide examples”are measurable and observable indicators

Achievable – this is appropriate for an introductory level course

Result-oriented – it focuses on the result (describe/ provide examples) rather than the process

Time-bound – students know that this is a skill they should master by the end of this unit

How to Write Effective Learning Objectives

As you create your learning objectives, think in terms of what evidence students will provide to demonstrate a level of mastery of the objective. A well-constructed learning objective consists of two parts: an action verb to make the type of learning explicit + the object.

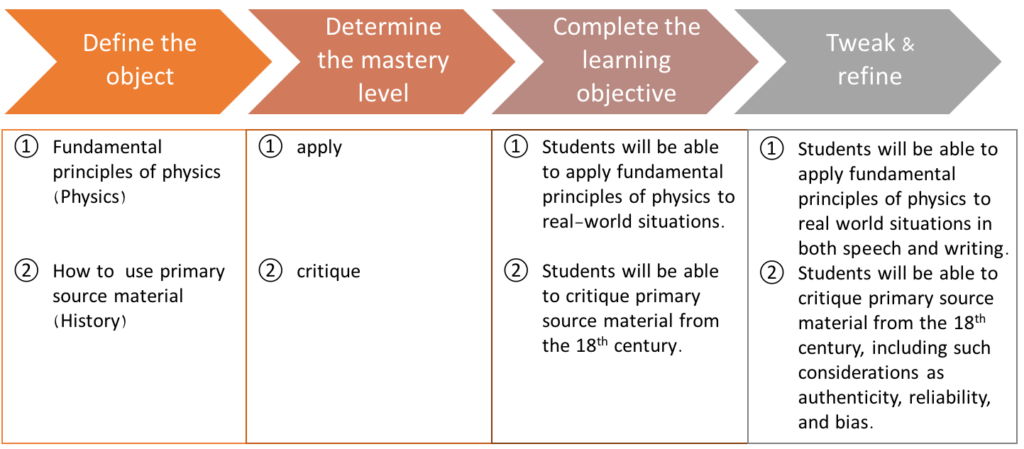

To write well-constructed learning objectives, you might follow the following the steps:

Step 1: Identify the object

(think about skills, knowledge, attitudes, abilities to be gained).

- Example 1: Fundamental principles of physics (Physics)

- Example 2: How to use primary source material (History)

Step 2: Determine the mastery level.

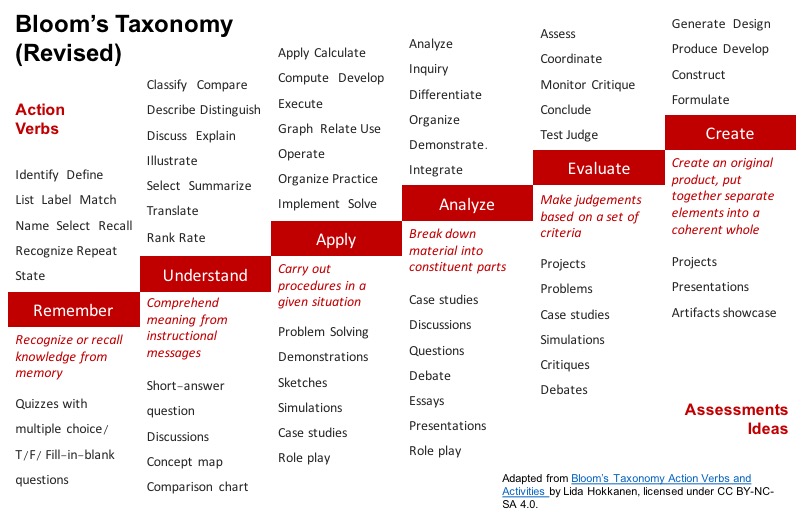

Determining the action verbs can be a tricky task. Benjamin Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives can be an extremely useful framework for determining what level of cognitive activity a learning objective falls into and matching that level with appropriate forms of the assessment.

- Example 1: apply

- Example 2: critique

The revised Bloom’s taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001) has six categories, from less complex on the left to more complex on the right:

Step 3: Complete the learning objective statement.

- Example 1: Student will be able to apply fundamental principles of physics to real-world situations.

- Example 2: Student will be able to critique primary source material from the 18th and 19th centuries.

Step 4: Tweak and refine your learning objectives

(using the Learning Outcome Review Checklist from Cornell).

- Example 1: Student will be able to apply fundamental principles of physics to real-world situations in both speech and writing.

- Example 2: Student will be able to critique primary source material from the 18th and 19th centuries, including such considerations as authenticity, reliability, and bias.

Implementing Learning Objectives

Align your course components with learning objectives

Even the best-written learning objectives are useless unless they relate to the actual instructional content, activities, and assessments of the course. If the course content and assessments are not aligned with the learning objectives, instructors will not have the appropriate data for determining whether students are meeting the desired goals. Students will feel confused or frustrated by the mismatch between the course objectives, evaluation, and content. The action verbs can help instructors review the alignment between their course components.

Here is an example:

Misaligned objectives & assessments

- Learning objective: Student will be able to compare and contrast the benefits of qualitative and quantitative research methods.

- Assessment: Write a 500-word essay describing the features of qual and quan research methods.

Well-aligned objectives & assessments

- Students will be able to analyze features and limitations of various sampling procedures and research methodologies.

- Assessment: Comparison chart assignment.

Notice how the first example doesn’t require students to actually use any analysis skills, compared to the second example.

References

- Anderson, L.W., & Krathwohl, D.R. (Eds.) (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman

- Melton, R. (1997). Objectives, Competencies and Learning Outcomes: Developing Instructional Materials in Open and Distance Learning. London, UK: Kogan Page.

- Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.